It’s apt that Mimi Somjee named her furniture business Window to the Past – now WTP The Furniture Company. Having grown up here in the 1950s, this redoubtable woman is herself a window to a bygone era, and her home a reflection of a more gracious time. She shares what daily life was like then.

Where were you born?

In 1952 there was only one maternity hospital: Kandang Kerbau Hospital, now called KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital. My elder brother always teased me that I was born in a cattle pen, because that’s the original meaning of kandang kerbau.

Where did you grow up?

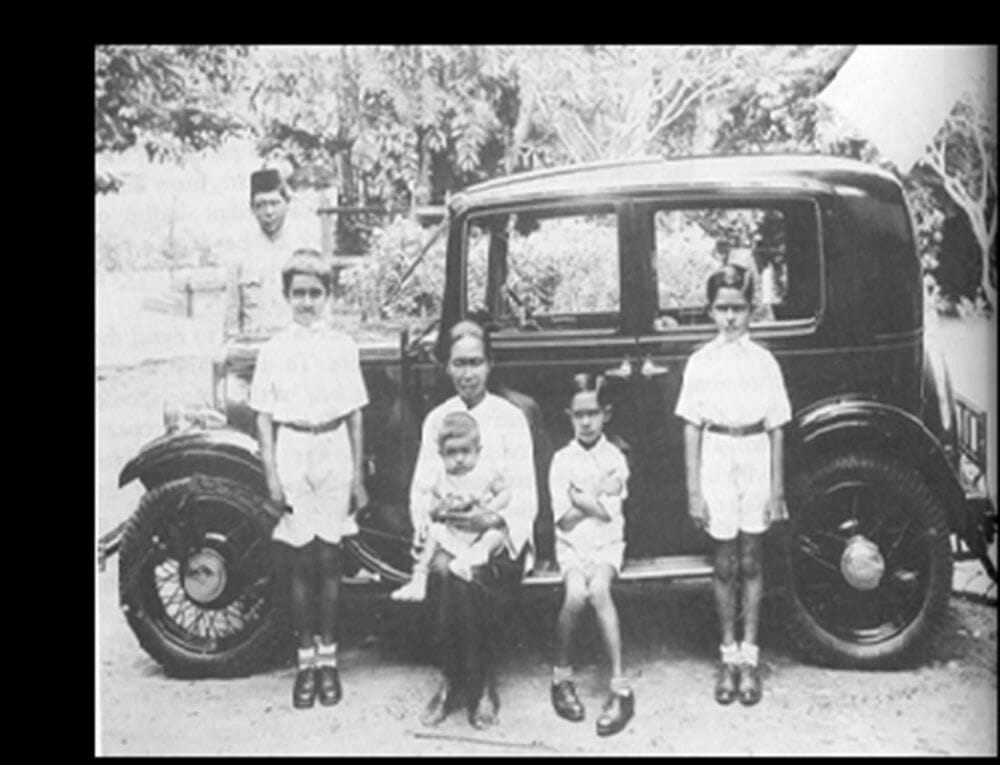

I grew up in a very privileged family, although at the time we didn’t realise how fortunate we were. Our family home was in Scotts Road, one of only eight bungalows. Incidentally, my father was born in 1925, in a house on the plot on which Tangs department store now stands. His father came to Singapore from western India in 1916 to assist his brother in his already successful trading business.

Our extended family lived in two big houses, one of which was later rented out. The one I grew up in had formerly been a dance studio, and was used as a pleasure house during the Japanese Occupation. My mother remembers that it used to have an exquisite Japanese rock garden inside the entrance hallway. The property stretched down to what is now the middle of Scotts Road; we had a tennis court, fruit trees, chickens and our own eggs.

Who was in the household?

Our house had a very strict hierarchy. My father had a black-and-white amah, “Amah Tua” (old amah), who had brought him and his brothers up, and she still ruled the house. What she said was law; if she said no to something, it didn’t help to appeal to Grandma. Under Amah Tua were the cook and the cook’s helper, then a woman who made beds and did the ironing, and finally the baby amah, my brother and me – the lowest of the low.

Father’s office staff also had their residential quarters on the premises, but I don’t remember them eating at our table. In fact, as children we didn’t even eat at the big table: we had our own little table and ate at different times from them and went to bed at 7.30pm in the old-fashioned way.

What are your earliest memories?

Playing in the garden with the children of our staff and our neighbours. The syce, or driver, had his own house and garden with fruit trees next to the gate; we played with his children every day and they came to our birthday parties.

They were very kind, hospitable people. We didn’t understand then why our mother became annoyed when we stayed for meals with them – the food was so delicious! – but it was because she was concerned that they couldn’t afford it. So whenever we ate at their house, we’d have to take them a gift the next day.

What did your family do?

My grandfather founded R Jumabhoys & Sons, a big trading business with interests in shipping. My dad worked in the same trading and shipping company. The family business expanded into real estate, starting in the early eighties with the development of our property into Scotts Shopping Centre, which is now Scotts Square. My father’s brainchild was The Ascott serviced apartments, both here and abroad – in London, Bangkok, Jakarta and Kuala Lumpur. In the late 1990s, however, after three generations of family feuding about the control of the business, Scotts Holdings was lost to the family.

As a child of one of Singapore’s elite families, how did you live?

It was an enchanted life. As children, we weren’t allowed to take part in the grand garden parties and dancing parties that my parents held, but we’d sit on the steps looking down at the women in their beautiful dresses and the waiters running around.

My mother Amina was no socialite, however. Far from being your typical Indian village bride, she was studying for her Master’s degree when she met my father in 1949, and wanted to be a lecturer, but women from rich families did not work in those days. As she was only allowed to volunteer her services, she became the captain of the Girl Guides at the Raffles Girls School; she also worked tirelessly to raise money for the poor and needy, especially orphans.

She was an unusually hands-on mother, in fact, and didn’t leave the baby amah to do all the work. She never accepted lunch invitations, because she wanted to be home for her children after school, and she used to drive us everywhere herself.

Where were you educated?

I went to the wonderful Methodist Girls’ School, which used to be behind Cathay Cinema, and my brothers went to the Anglo-Chinese School that my father and his brothers had also attended.

I still have the same friends today that I had when I was six years old, most of them from a similar background to my own. But ours was a government-aided school, and my classmates came from all walks of life; some lived in poor kampongs, others in crowded Chinatown shophouses. We didn’t really understand how lucky we were. We thought kampong life was fun and glamorous – you could run around barefoot with the chickens!

Coming from a Muslim family, we were all brought up with both Muslim principles and strict Methodist principles from school: a clear idea of right and wrong, and how you had to love everyone, be humble, be good and work hard. However, the one bad thing about a girls’ school like ours was that the clever girls were in the science class, and because we wanted to be clever, we all strove to be in the science class. I ended up with four A Level science subjects.

My diligent elder brother made it to Oxford University at a time when only two Singaporeans were admitted each year. Being a sporty tomboy, I didn’t study very hard, and to encourage me my father said I could join my brother there if I passed the entrance exam and secured a place – which I did. But he said I had to choose a course that wasn’t offered in Singapore, so I read for a natural science degree in physics!

What do you remember about Singapore in the fifties and early sixties?

Chinatown was great fun, so busy and crowded; we’d go there with our amah for Chinese New Year to buy special fruit and candies. She would also take us to her temple, and sometimes to her attap house in Balestier Road, which was farmland in those days. We also attended wayangs with her and diligently observed all the Chinese festivals.

By 4pm you’d done your homework, and all the children played together at one of two pre-arranged locations. We played rounders, hopscotch and five-stones, and also a game called kuti-kuti, with little plastic collectibles. The “pi-pop” man on his bicycle cart sold them, together with everything else that a child could want, such as sweets and chewing gum. Then there was the mee pok noodle man, who made his own special sound as his cart approached, as did the satay man and the kueh tut tut man.

My grandmother took me with her to visit her friends on Emerald Hill. I went everywhere with my grandmother, I suppose because I was the only granddaughter. The old ladies would sit and chew betel and chitchat, while the children played on the street. That’s where I ate my first yue cha kueh, fried up by an itinerant hawker.

I was never allowed to take the bus, though, and neither was my best friend Mei Ling – though we did so illicitly for the sheer fun of it. I only found out years later that it was because there’d been a kidnap threat on my father’s life.

Who were your friends?

Some of our friendships went back generations, and as we grew up we all went to the same parties, belonged to the same clubs and lived the same lifestyle. Every year, we went to Christmas parties at Singapore Island Country Club, and later to the teenage balls.

Though we were Muslim, our friends were drawn from every community and though we all lived in different pockets of Singapore, we all celebrated each other’s festivals. My grandmother was very friendly with the Jewish, Arab, Indian and Chinese communities. In fact, the term “multi-racial Singapore” was first used in Parliament by my grandfather, who served in the Legislative Assembly.

My father was friends with David Marshall, Singapore’s first Prime Minister, and I remember going to his beautiful house in Tanah Merah on Sundays. He was a lovely man. He’d take us swimming, and afterwards we’d have homemade doughnuts.

Where did you shop?

We went to Tekka Market with my father on Sundays to buy fresh fish, and he still does that with his grandchildren today. Cold Storage creameries had the best knickerbocker banana skyscrapers and the like; curry-puffs from Honeyland milk bar and Polar Café, and éclairs from the Adelphi Hotel.

Robinsons was the ultimate shop for outfits for special occasions. There was another called Whiteaways, and the Great Wall specialised in little girls’ smocks and party dresses. For everyday wear, we had a tailor who came to the house. The cobbler came to the house too, and so did the hairdresser, and the massage lady. I also remember a jeweller who sat on our verandah making new jewellery for the family, some of which I inherited from my grandmother.

My parents never gave us more pocket money than anyone else; if we needed extra money, we could work for it. My mother had inherited a lot of English sterling silver, and we could earn extra money by polishing it, by washing cars or by sweeping leaves in the garden. In the school holidays, we’d work as peons in my dad’s office. In one month, I made $50 and bought myself a really nice watch, which I still have.

Where did your love for silver come from?

I inherited quite a lot of it – my mother even gave talks on silver jewellery – but I also picked up bits and pieces along the way. I’m a real collector at heart.

We thank Mimi Somjee for revealing some of her fascinating memories and insights into a way of life that is no longer to be found in Singapore. Given her rarefied upbringing and special experiences, it’s appropriate that she has followed her passion for distinctive collectibles and furniture, both antique and contemporary. It’s also heart-warming to see how she makes every effort to share her creativity and knowledge with her customers from all over the world.

For more helpful tips, head to our Living in Singapore section.

Top 20 bars for cheap drinks!

Where to find work shoes for men

Love animals? Work at ACRES