September marks the 75th anniversary of the end of World War Two and the surrender of Japan in Singapore. Writer and historian LIZ COWARD looks at the events that unfolded around this time in 1945.

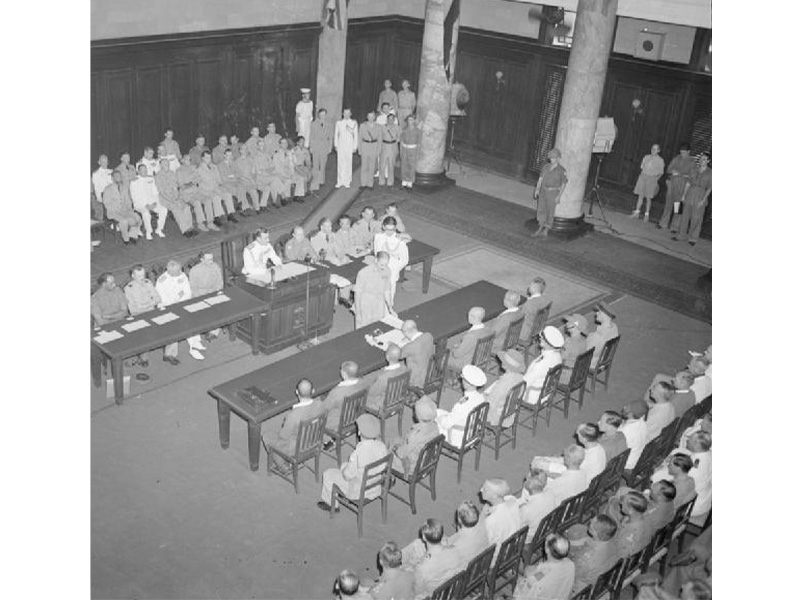

On 12 September 1945, General Itagaki, Commander of the Imperial Japanese Seventh Area Army, signed the official surrender of the Japanese Expeditionary Forces in the Southern Region, at the Municipal Building, Singapore. It would be the last major surrender ceremony of World War Two, a conflict that had cost over 60 million lives and led to the emergence of a new world order.

How it happened

Japan was the last nation in the Tripartite Pact to surrender – Italy had negotiated an armistice in 1943, and Germany had fallen in May 1945. The Allies warned Japan that, “the prodigious land, sea and air forces of the United States, the British Empire and China” would be directed towards it unless it offered its unconditional surrender. This was anathema to the Japanese forces, whose notion of bushido (a code of honour and ideals) meant that they believed it was better to die than be taken prisoner.

The Allies therefore had to decide how best to bring World War Two to a swift conclusion. They took into account Japan’s fanaticism, and its use of biological and chemical weapons and Kamikaze attacks. They ultimately decided on a land invasion coupled with the use of the newest addition to its arsenal, the atomic bomb. It was hoped this would shock Japan into submission.

Hiroshima and Nagasaki

The first atomic bomb was dropped on the Japanese mainland at Hiroshima on 6 August. Around 100,000 people died instantly. Many more thousands subsequently died from radiation poisoning, burns and shock. Japan was warned that if it failed to surrender immediately, “it may expect a rain of ruin from the air, the like of which has never been seen on this earth.”

Two days later, the Soviet Red Army surged into Manchuria and northern China with more than 1,600,000 men, and invaded the Kurile Islands and Sakhalin north of Hokkaido.

On 9 August, the Japanese Supreme Council met to consider a surrender. The Imperial General HQ refused. Later that day, a second atomic bomb was dropped at Nagasaki.

Start of the surrender

Emperor Hirohito recalled the Supreme Council and said they should offer an unconditional surrender provided the imperial house and its succession was preserved. Again, the military leaders refused, so the Allies continued their land offensive. On 14 August, the Emperor insisted that Japan should surrender and he would broadcast a message to that effect to the nation.

That night, he was forced to hide in the Imperial palace when it was attacked by officers determined to destroy the recording equipment. They failed, and the next day Hirohito announced that, “despite the best that has been done by everyone… the war situation has developed not necessarily to Japan’s advantage, while the general trends of the world have all turned against her interest…this is why we have ordered the acceptance of the provisions of the joint declarations of the powers.”

His announcement was greeted with mixed feelings. Surrender ran contrary to bushido spirit and the exaltation “not to survive in shame as a prisoner”. Some pilots decided to launch one final glorious suicide mission against American forces. They were shot down, but it was clear that a peaceful surrender was far from guaranteed. This was uppermost in the mind of Lord Mountbatten, Supreme Allied Commander SE Asia Command (SEAC), within which area Singapore fell.

The situation in Singapore

Singapore was the jewel in the crown of Britain’s Southeast Asian colonies, so its rapid invasion had been a priority. Following the Japanese surrender, these plans, Operation Tiderace, were converted to re-occupation. However, before it could commence, Itagaki, commander of Singapore’s garrison of 70,000 men, had to confirm that he intended to obey the Emperor’s orders.

Alarmingly, he didn’t respond to SEAC requests for confirmation. So, on 19 August, Captain O’Shanohun, SEAC staff signals officer, parachuted into Singapore to find out. He discovered that the Japanese intended to surrender – but also that their concerns had been well founded. Only the previous day, Itagaki had met Field Marshal Count Terauchi (Mountbatten’s equivalent) and expressed his reluctance to follow the Emperor’s orders. He was told, in no uncertain terms, to obey the Allied commander’s surrender instructions. Itagaki confirmed that he would do so to O’Shanohun.

On 22 August, Itagaki informed his generals and senior staff that they would have to obey the Allies and keep the peace until they arrived. That night, 300 Japanese officers committed suicide at the end of a farewell party at Raffles Hotel.

Final formalities

The surrender of Singapore was confirmed in Rangoon on 26 August. General MacArthur, Supreme Commander of the Allied Forces, wanted to take the first Japanese surrender, so the Rangoon document was described as a local agreement.

On 2 September, MacArthur accepted the unconditional surrender of the Japanese Imperial General HQ, the Japanese armed forces and all the armed forces under Japanese control wherever situated. Shortly afterwards, permission to commence Operation Tiderace was received. On 4 September, detailed operational terms of the Singapore surrender were agreed on the HMS Sussex in Keppel Harbour.

The local population was unaware of these momentous events, so when soldiers from the 1st Punjab Regiment came ashore on 5 September there was no one there to greet them. Upon arrival, they fanned out from the docks to occupy key positions, including the surrendered personnel camps. By midnight, the British and Commonwealth troops were back in charge and 35,000 Japanese troops had been evacuated to camps in Johor.

A stalling tactic?

The re-occupation of Singapore had proceeded smoothly, but there was a last-minute hitch to the meticulously planned official surrender ceremony. Terauchi, key signatory of the surrender, was too ill to attend. As supreme commander of the Japanese forces in Southeast Area command, his presence was vital to give legitimacy to all the previous and subsequent surrenders.

Mountbatten was suspicious of a stalling tactic, but Terauchi had indeed suffered a stroke and Itagaki was appointed to sign on his behalf. Hence, on 12 September, it was he who surrendered to Admiral Lord Mountbatten, officially restoring Singapore to the British Empire.

Liz Coward is the author of Blood and Bandages – fighting for life in the RAMC Field Ambulance 1940-46, which you can buy through the Expat Living website at expatliving.sg/ magazines-guides-books.

This article first appeared in the August 2020 edition of Expat Living. You can purchase a copy or subscribe so you never miss an issue!