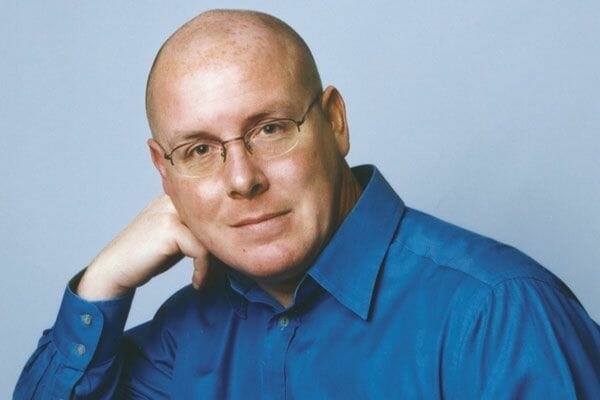

He’s made millions, lost billions, brought down a bank, been on the run, spent four years in prison, fought cancer and commercially managed a football club. NICK LEESON was the original Rogue Trader. In this interview he talks about living in Singapore and what lessons he’s learnt.

Your book has been reprinted many times and made into film. Why do you think people are so interested in the story?

It’s very difficult to put my finger on why so many people find the story interesting. There is a tremendous amount of human interest. Different aspects of the story attract attention from different people. It’s a story initially of an ordinary person doing very well, achieving more than most people could imagine, getting himself into a difficult position, making some very bad decisions, compounding those with even worse decisions and ultimately losing everything. At the forefront there is the collapse of a 233-year-old merchant bank, a loss of a sum of money that most people find astounding and a man hunt for the person involved; me. The story took centre stage in the international media for a time and many people can recount where they were when it broke. The story defied logic at the time and captured the imagination of many. There were protracted court battles in Europe and then a high profile return, the best part of four years in a maximum security prison in Singapore, a battle with cancer and ultimately a release and the opportunity to rebuild both myself and a career.

I often say that I’ve experienced an awful lot in my first 33 years. I’ve encountered most of life’s stressful events in a very short period of time, in extreme circumstances and managed to survive. It’s a story of incompetence and negligence on a grand scale, my own very much at the forefront during my time at the bank. But it is also a story of triumphing over adversity and rebuilding.

You’ve often stated that the events in Singapore are the most embarrassing in your life but if you could travel back in time, how much would you change?

Everybody wants to be known and remembered for good or successful things. That will never be the case for me. I will always be the Rogue Trader and described as a “disgraced banker” or some such adjective. Success was always the thing that drove me; ultimately it became way too important and had a large part to play in the way that I reacted to certain situations. Being remembered as the protagonist for the collapse of Barings Bank will always be embarrassing. It is certainly not what I wanted to happen.

Part of the recovery from that time has been accepting that and coming to terms with it; it is impossible to move on otherwise. I think I have done that. Prison was a fairly worthless exercise other than as a form of punishment, a punishment that was wholly justified but it did change some of my approaches to life and the way that I think about things. Wishful thinking, as described in your question is probably the most wasteful and debilitating thing that anyone can do. I spent many days, 24 hours a day, thinking about the things that I could have changed. The simple fact is that you can’t and the longer you spend thinking about things that you could have done differently, the less time you are spending accepting what happened and moving on. In a very negative environment, wishful thinking accelerates the decline into depression so you have to arrest that decline and change the damaging form of thinking very quickly. Remorse is an overworked word in this episode and every time I hear it I worry that it has a hollow sound. I am truly remorseful; there is nobody that wishes it hadn’t happened more than me but, more than anybody else, I also have to face the reality that it did happen. Acceptance and responsibility are key components of any form of recovery. I no longer engage in any form of wishful thinking.

Do you think Time magazine’s “Ego & Greed” cover was a too simplistic interpretation of the events? Would “Fear of Failure” have been a more apt tag line?

Both “Ego and Greed” and “Fear of Failure” have a high degree of relevance. I think a large number of onlookers would immediately veer towards ego and greed taking over. I know that my fear of failure was equally as alarming as my need for success. I have had to temper or blunt both since that time. I couldn’t tell anyone what was going on, nobody at work or at home because it would have highlighted my own failure and at the time that was the one thing that I couldn’t come to terms with. A psychologist that I wrote a book with characterises my need for success differently to my need for status. Status came with the deceit because everybody bought into the picture that I was painting using the 88888 account. The psychologist ends the first chapter of the book on status with the statement “When an immature person has status, they will do anything, absolutely anything to protect it.” To me the statement embodies an awful lot of what happened to me during that period.

There was no plan; I reacted to situations on a day-by-bay basis. I lived in fear 24 hours a day at first but when that knock on the door didn’t come for an extended period I slowly started to realise that I had time to correct the situation.

Time in Singapore

Did you enjoy your life (outside of work) in Singapore and Jakarta? And what’s the most extravagant thing you did during your time as a trader?

I lived in Tokyo, Hong Kong, Jakarta and Singapore during my time in Asia. But I was only in Tokyo for a relatively short period of time. I thought the lifestyle in Hong Kong was far too colonial and it didn’t really suit me so I asked to be posted elsewhere. I have been back a number of times since and find it far better now. Jakarta was always my favourite; it was very under-developed, very raw when I moved there in 1990. We had a driver who accompanied us everywhere and there were a very limited number of places that we were allowed to go to. We adhered to the rules for the first three months or so and then started to cut loose. We worked hard, partied hard and had a great time. We were very well looked after but for me it was always important to socialise with locals. I had many Indonesian friends and would probably spend more time with them than the wider expat community. Singapore was clean whereas Jakarta was dirty. Singapore was regulated whereas Jakarta was dangerous but the standard of living in both as an expat was exceptionally high. Career wise there was little else that I could achieve in Jakarta at the time so I moved back to the UK and then on to Singapore.

Extravagant is not a word that I would associate with myself. I bought a rather inexpensive (comparatively speaking) Rolex when I lived in Singapore. I have a different one now but still one of the less expensive varieties. I am not ostentatious in the slightest way. I did have a car in Singapore but there was nothing special about it. There was one stupid, drunken night in a nightclub that I think was called Brubakers when I bought twelve bottles of Krug champagne. Four of them were returned to me about seven years ago; I opened one, it tasted horrible so I binned the rest.

Harry’s on Boat Quay is still a popular haunt for city types. When you went there to have a drink at the end of the day was it done with a sense of celebration or nervousness?

It’s one of the great myths of my time in Singapore; I very rarely went to Harry’s on Boat Quay. Yes, it was a popular place with expats. Yes, I was an expat, but as I mentioned previously I preferred to socialise with locals that worked for me. If we did go for a drink after work it tended to be to bars at the other end of Boat Quay. One in particular was called Big Ben, it had a pool table, you could play darts and we knew the bar staff reasonably well. If a client or somebody from London was visiting, I might have had one drink in Harry’s but that really would be it.

At the time, I was living two lives; the reality of what was happening on the trading floor as opposed to the lies that I was positioning to everyone else. The last thing that I wanted to do at the end of the day was dissect how the trading day had gone which was typically the subject of discussion amongst the expats in Harry’s. I wanted to get away from all that.

I’ve lost count of how many hundreds of people who have told me that they drank in my favourite bar in Singapore or tried the “bank breaker” cocktail. Harry’s was one of the successes of that period; a couple of the traders in Japan have gone on to be extremely successful as well.

When you first fled Singapore for Malaysia, did you think that you would be able to lie low forever?

On the 23rd February 1995, I was questioned over the discrepancy in the trading position at SIMEX. The discrepancy had existed for the best part of three years but nobody had done this very simple reconciliation. It’s something an eight-year-old could do. When confronted, I had no explanation, no answers, and no way to conceal the illegal account. I had two options; face the music or run. I chose the latter, there was no prior thought attached to it at the time. It was quite simply a fright and then flight mentality. Self-preservation was at the top of the agenda and being caught in Singapore and limiting my options (no pun intended!) was very much at the bottom.

As with the previous three years, there was no plan. At the time there was only one flight that you could buy a ticket for at the airport; the shuttle to KL. We bought tickets on the first flight out, late afternoon, early evening and went to a hotel, the Regent in Kuala Lumpur that we had stayed in recently. I knew that there were going to be significant losses, I couldn’t have told you at the time what the amount came to but I certainly didn’t expect the bank to collapse. I made a couple of calls back to friends in Singapore that I could trust and suddenly the enormity of the situation started to hit home. We just survived hour by hour and reacted to events as they presented themselves. I think that it was well known that I was in Malaysia. I have no idea how I managed to pass through passport control in Kota Kinabalu a few days later.The plan at that stage was to get back to a Western country and instruct a lawyer.

Are you still in contact with some of the people that you worked with in Singapore?

I am still in contact with a number of people from that time. None are still in Singapore; they have all moved on as markets have changed and opportunities have moved. It would not be appropriate to name any of them. When I was diagnosed with cancer in prison, three of the people that worked me for on the trading floor came to visit. I think they all had the advantage of knowing me the person rather than the banking pariah that a lot of people have heard about or read about.It’s a strange thing trying to tally the two. I normally don’t try but just yesterday my twelve-year-old stepson asked me how I could have got so well-known through working in a bank. He asked was I some kind of “banking superstar”. I’m going to have to give this one some thought.

During your time in Changi Prison, were you an influential figure or an outcast?

In some way I think I was revered by the other prisoners. They thought I was a mastermind criminal and had stolen a lot of money. It elevated me to a certain level within the hierarchy of the prison. Everyone in the Singaporean prison thought that I was in with a member of one of the Chinese or Malay gangs.

I was the anomaly. I was left to my own devices pretty much. My movements were heavily supervised by the prison guards.

The prison system is very tough. That may have been because my entire sentence was in a maximum-security facility but for the majority of inmates it was a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Given the fact that the likes of Kerviel and Adoboli have gone on to make greater financial losses than yourself, do you think the banks have learnt anything from your experience?

Unfortunately a number of banks have been slow to learn the lessons presented to them. In my opinion this is usually because the systems and controls cost money. There is no industry where the fundamental attribution error is stronger. Banks know that another episode of rogue trading is around the corner but they don’t believe that it is going to happen to them. That makes it okay. Hopefully this is now starting to change as much of the world recovers from a global banking and credit crisis that could have been avoided.

And do you still trade?

I think the amount that I trade these days is grossly overstated. It makes good copy for newspapers and they like to make a little more of it than it is. It will sound heavily over – clichéd but I really do only trade with money that I can afford to lose. I’m far more disciplined than I was years ago and set tight stops to any position that I do enter.

What skills did you learn at Barings that transferred well to working at Galway United? And are you on the look out for a new football club?

I’d like to think that I have always had good social skills. I have found it equally easy to survive on a trading floor, building site or football club. I had no longing desire to work at a football club, the opportunity presented itself and I took advantage of it. Whilst my need for success was a contributory factor in all that happened in Singapore, I am now more than aware of that and have had to temper that need. It is however, important to be able to measure success and reframe how you measure success. In Singapore in the 90s, success was making all the tough decisions, making more money than anybody else and rapid promotion through the organisation. Sounds sad but at 25 years of age that was what I genuinely believed. The same amount of success can also be derived from putting food on the table for your family to eat. I have had to reframe many of the ways that I view my day-to-day existence; it makes for a simpler and way nicer way of life.

How does a typical day unfold for you these days?

My primary source of income comes from talking at dinners and conferences. I am a more actively sought after-dinner speaker than I was at the time of my release from Singapore which would suggest that after thirteen years I must be quite good at it. It is reasonably lucrative so I am able to pick and choose where and when I want to work. I write regularly for a couple of publications in Ireland and am affiliated to a couple of educational bodies. I am often asked to comment on radio and television on a number of matters and do so.

I have a very healthy work-home balance, and am not consumed by the world of finance as I was. I walk the dog, go to the gym and am very heavily involved in the upbringing of our three children. No day is the same but thankfully no day is anywhere near as frenetic as it was in Singapore.

What advice would you give a trader heading to Asia to make his name?

Go, you’ll have a fantastic time but remember two things: firstly, everyone makes mistakes but if you do make a mistake, never ever try to hide it. I think organisations should create an environment where employees know that mistakes are expected but what will not be tolerated is if you choose to hide them.

Secondly, wherever you are working, you are surrounded by people who have found themselves in similar situations or know how to deal with it. The first time that you encounter something that you can’t cope with, please ask for help and advice. When things started going wrong for me in Singapore, I was 25 years of age. I thought I could cope and perceived asking for help as a sign of weakness. I was wrong on both counts. I couldn’t cope and asking for help and advice is a sign that you want to do things correctly.

It’s often said that great things come from unexpected places. What has been the best unintended result from your experiences in Singapore?

It’s very difficult to find many positives from that period. I made a mess of my life, went to prison and developed cancer, so there wasn’t too much that was uplifting. I discovered that knowledge is power, especially where your health and wealth is concerned. I knew nothing about cancer when I was diagnosed in 1998. I had to learn very quickly and change from being a passive recipient of information to being an informed part of the recovery. That was so very important.

My approach to life and the way that I think about things did however change. I learnt that wishful thinking is a waste of time. I also talk about what I am feeling and experiencing more than I ever did in the past. Everybody else has an innate ability to cope, no matter how bad it looks initially. There are things in your life that you can influence and things that you cannot influence. I do not allow the things that I cannot influence to worry me and I try and accept responsibility for everything that I do.

For more helpful tips head to our living in Singapore section.

Don't miss out on the latest events, news and

competitions by signing up to our newsletter!

By signing up, you'll receive our weekly newsletter and offers which you can update or unsubscribe to anytime.