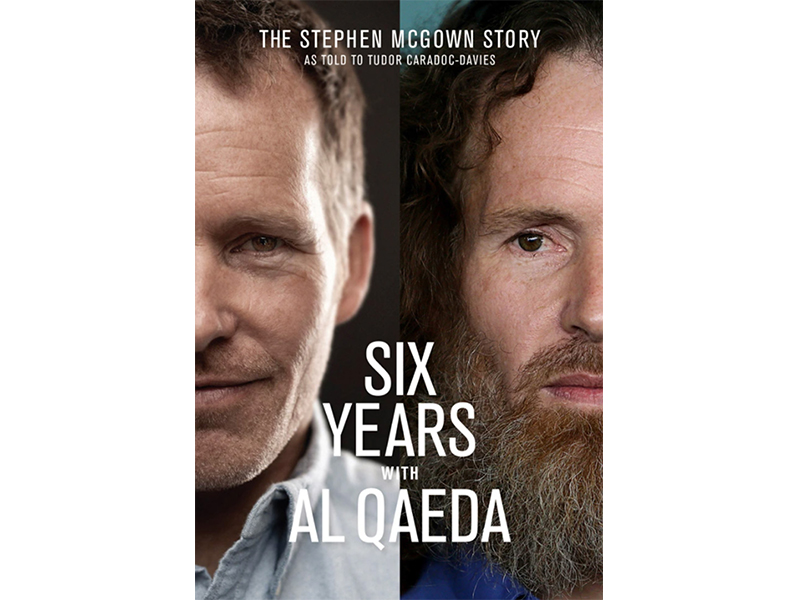

South African STEPHEN MCGOWN holds the undesirable record for being Al Qaeda’s longest-held prisoner. His astonishing story of mental strength, grit and physical resilience sheds light on the endurance of the human spirit.

I recently heard Stephen speak to a Singapore audience about his six years held in captivity, while getting an insight into one of the world’s most feared terrorist organisations. Despite living through a nightmare, his gritty story inspires us to “reframe” our attitude, as he proves that we can endure more than we think.

A long journey home

Stephen’s nightmare began in 2011 when he and his wife were relocating from London to Johannesburg. He had planned to motorbike his way back to South Africa from the UK while his wife took a flight. Little did he know that he wouldn’t see her or his family for the next six years.

One fateful day in Timbuktu, Mali, Stephen was in a restaurant when he and a few other hostages were taken captive by Al Qaeda. They were driven for 15 hours into the desert, where they set up camp away from civilisation and aerial surveillance.

Describing the journey as “the greatest chess game of my life”, for the next six years, he was never far from death.

Negotiations and videos

His captors embarked on long, protracted negotiations for Stephen’s release. They varied their ransom demands, initially asking for over 11 million dollars. Though no ransom was apparently paid, Al Qaeda played a waiting game, holding out for negotiations or a prisoner or cash exchange. Their objective was to ensure their prisoners didn’t escape and were not found. They would also go to great lengths to hide their positions from Western surveillance, including burying oil drums, water and cars.

To encourage (or provoke) ransoms to be paid, the captives would regularly have to film “proof of life” videos. Stephen filmed around 20 of these, in which he was made to wear pink/orange captive uniforms while Al Qaeda members stood behind him with large guns. The objective was to humiliate the captives, though Stephen was just relieved they weren’t virtual public executions.

Daily life Al Qaeda would move their positions every two weeks or so – Stephen was held in around 150 camps across the Sahara Desert. They were always in the middle of nowhere, far from civilisation, and completely off the grid. During these moves, Stephen would be blindfolded, never knowing where he was going or whether he’d arrive alive. He would be made to sit with little or no movements for days and weeks at a stretch; this led to extreme pain in his joints, so that he couldn’t pick up a bottle of water or sit cross-legged. In the end “standing was better than sitting” and “walking was better than standing”. The desert conditions were harsh. The blazing sun would blister his skin, and the extreme winters were bitterly cold. He lived through sandstorms and thunderstorms, and would curl up and grit his teeth until they passed.

Food and water shortages were frequent. He would drink water from large fuel drums that hadn’t been cleaned properly. “There was always a residue of diesel on the surface that gave me incredible headaches,” he says. “I realised quite early on that the impact of mental anxiety is far greater than physical pain.”

Survival and acceptance

When arriving in a new camp, the captives would try and build their new “home” in whatever patch they were allocated. If there was a tree, they would throw a blanket over the branches to create a shaded area. Sometimes, they were lucky enough to build a hut using sticks and grass.

In 2013, Stephen was “on the brink of insanity”. Malnourished and with aching joints and painful eyes, he would listen to his heartbeat to remind himself that he was still alive. He credits his sense of purpose and attitude for his survival.

At one stage, he decided to convert to Islam to understand his captives at a deeper level. This conversion allowed him to sit in a circle with the Al Qaeda men and create a dialogue. He learned how to speak, read and write in Arabic, and could recite more than 30 prayers.

He also taught his captors French, mathematics and geography; he felt that, without their guns, Al Qaeda were also ordinary humans at heart.

Health and attitude

Remaining physically strong became a priority. Stephen and his fellow captives devised exercise routines to keep fit and lift spirits. So they would run in circles for an hour or do a “bootcamp” routine to keep their joints moving and their hearts from breaking.

On two occasions, he developed large painful sores on his back. One of those times, he asked a fellow captive to cut out the rotting flesh using a razor blade and antiseptic. “Five minutes of pain was so much better than three or four months of mental anguish,” he says.

Such experiences taught him how strong humans actually are. “Sometimes we need to grit our teeth and push through, because we are capable and we can achieve.”

Indeed, he wanted to exit the desert a changed, stronger and more positive human; so he tried to use the time to “grow”. “It’s our attitude that separates us and determines how we cope. Some people give up too easily.”

“You are your attitude,” he continues. “What we see and believe about a situation is our attitude and thus our reality”.

Stephen would visualise talking to his wife to keep the flame of hope burning. He’d wrap his scarf between his fingers to imagine holding her hand. These fantasies helped him maintain a connection to the outside world.

To avoid falling into self-sabotaging habits, he’d also write what he was inspired by and grateful for onto a milk carton. This helped him stay positive with big-picture thinking during the darker days. There were even some “funny” moments that Stephen can recount, which paradoxically helped him mentally survive his ordeal.

Re-joining the world

At age 42, six years after he was snatched from civilisation, Stephen was randomly released from captivity. Re-joining “real life”, he faced initial anxiety and triggers, as well as getting used to a world that now had Uber and Airbnb. Sadly, his mother passed away just two months before his release. Reflecting on her passing, he says, “She was an amazing lady and I can imagine the difficulties she went through.” Despite this, he doesn’t want to harbour resentment towards his captors. “I will forgive; I will move on.”

The parting words he gave to listeners in Singapore was to encourage us to get in touch with ourselves and find out what is important to us. Have patience and have gratitude, he suggested, before reminding us how strong and capable we all actually are.

Six Years With Al Qaeda: The Stephen McGown Story is available on Amazon.

This article first appeared in the July 2021 edition of Expat Living. You can purchase the latest issue or subscribe, so you never miss a copy!