Go on a treasure hunt to find the incredible street art in Singapore – or even be a part of it! There’s some amazing art, and it seems to be growing all the time with some cool modern ones popping up too. As part of the latest artsy adventure of Tanglin Trust School, here’s a look at some of the historic street art scenes around town – but spot the difference!

The continuing absence of theatre performances, concerts and large-scale events means we need to get creative in staying connected with the arts, both at home and at school. This might be a nice idea for a family adventure on a Sunday afternoon. There’s more information below on the artists and locations – see how many you can find!

Searching for Street Art

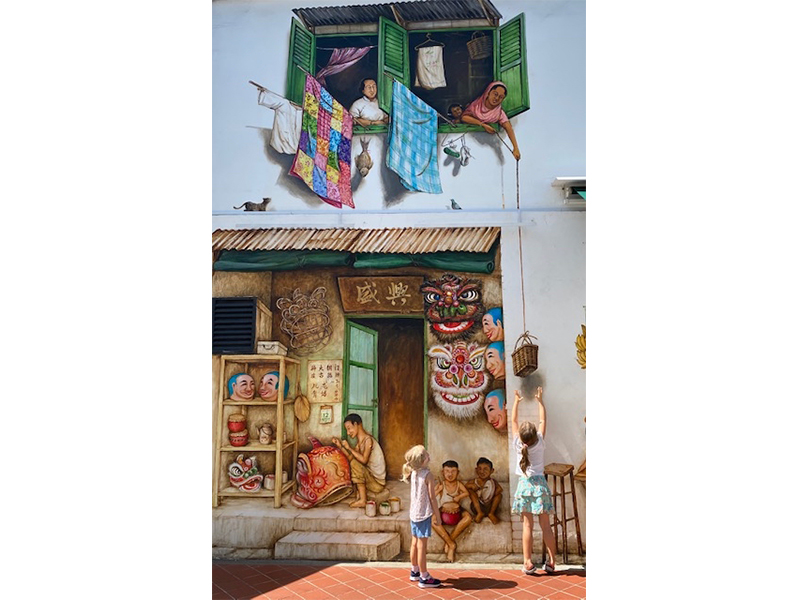

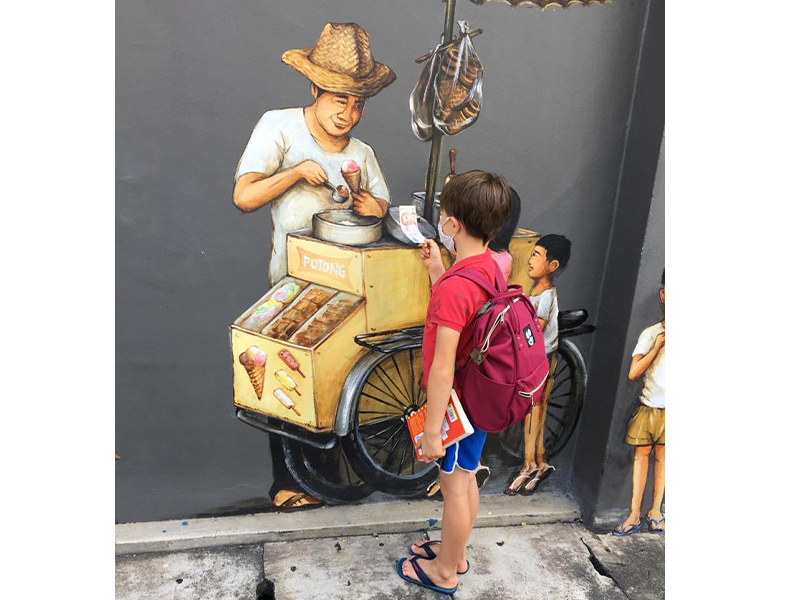

Though few know him by name, many will know his work. Street artist Yip Yew Chong (also known as YC) is the man behind a series of nostalgic murals dotted around Singapore. From the street-side Barber on Everton Road to Tuan Yuan Bak Kut Teh in Tiong Bahru, YC has created over 60 murals across the island that endearingly act as a portal into Singapore’s colourful past.

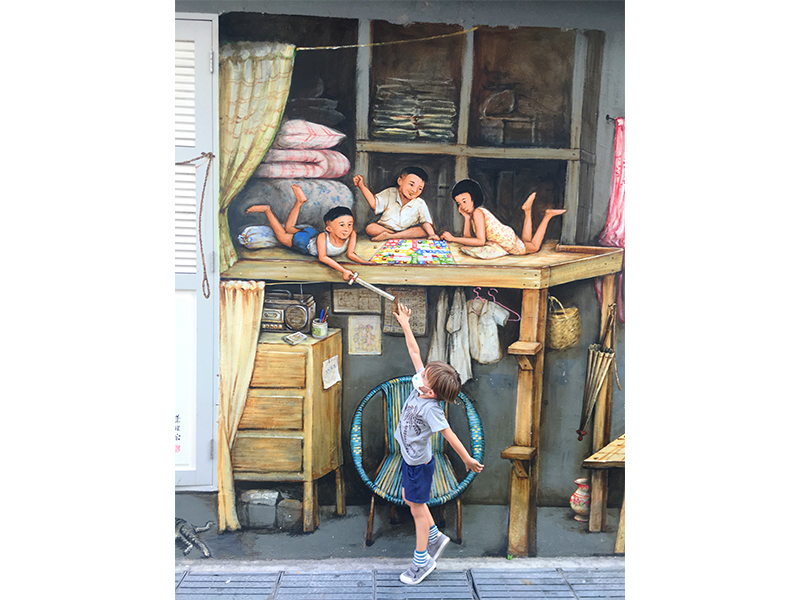

“I make art that tells stories, based on my childhood memories and travel adventures. I hope they’ll evoke other people’s memories and inspire them to tell their own stories,” says YC. “Children, in particular, see the nostalgic, real-life scenes, and get curious about how others lived – and they want to play a part.”

Inspired by YC’s work, and knowing children wouldn’t be able to cross any borders during their school holidays, Tanglin Trust School teachers challenged their students to take their families on a quest to find the murals across Singapore. The response was remarkable! With more than 200 entries submitted, Tanglin kids clearly revelled in the opportunity to travel in time and take a fun snapshot alongside an enchanting slice of Singapore culture.

To view all entries in Tanglin Trust School’s YC Art Challenge, visit tts.edu.sg/news-and-events/yc-art.

For more information about the artist, and to find a location map for your own adventure, visit yipyc.com.

This article first appeared in the January 2020 edition of Expat Living. You can purchase the latest issue or subscribe, so you never miss a copy!

Interested in seeing more? Here’s another feature we’ve done on street art in Singapore!